Differences Between Chinese and Japanese Calligraphy

Chinese and Japanese calligraphy are deeply connected due to their shared roots, but they developed distinct characteristics over time, influenced by cultural, linguistic, and philosophical differences.

1. Historical and Cultural Context

Chinese Calligraphy (書法, Shūfǎ):

Origins: Chinese calligraphy is the oldest tradition, originating over 3,000 years ago with oracle bone inscriptions (甲骨文) during the Shang Dynasty.

Philosophical Influence: Rooted in Daoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, Chinese calligraphy emphasizes harmony, balance, and spiritual expression.

Cultural Status: Considered one of the highest forms of art, alongside poetry and painting. Historically practiced by scholars (文人, Literati), it was a marker of education and social status.

Japanese Calligraphy (書道, Shodō):

Adopted from China: Introduced in the 5th–6th centuries through cultural exchange with China and Korea.

Development: Over time, Japanese calligraphy integrated kana scripts (Hiragana and Katakana), creating a uniquely Japanese aesthetic.

Philosophical Influence: Deeply tied to Zen Buddhism, emphasizing mindfulness, simplicity, and the meditative nature of the act.

Cultural Role: While highly respected, Japanese calligraphy became less formalized than its Chinese counterpart and more experimental, reflecting Zen ideals.

Biographies of Lian Po and Ling Xiang Ru by Huang Tingjian (草書廉頗藺相如傳 by 黃庭堅)

Letter to Suwa Daishin, Officer of the Shogun by Musō Soseki 消息 by 夢窓疎石筆

2. Linguistic Differences

Chinese Characters (漢字, Hànzì):

Complexity: Chinese characters are often more intricate due to their pictographic and ideographic origins.

Evolution: Includes a range of script styles (e.g., Seal Script, Clerical Script, Regular Script, Cursive Script).

Continuity: The characters remain largely unchanged in form within traditional Chinese calligraphy.

Japanese Writing System:

Kanji (漢字): Borrowed Chinese characters, sometimes simplified or adapted in meaning.

Kana (仮名):

Hiragana (平仮名): Curvilinear, flowing script used for native Japanese words and poetry.

Katakana (片仮名): Angular script used for foreign words and emphasis.

Integration: Japanese calligraphy often combines kanji and kana, creating visual contrasts and flowing compositions.

3. Aesthetic and Philosophical Differences

Chinese Calligraphy:

Structure and Discipline:

Focuses on the balance and proportion of each stroke and character within an invisible grid.

Reflects Confucian ideals of order, precision, and moral cultivation.

Variety of Scripts:

Offers a wide range of styles, from the formal Seal Script (篆書) to the expressive Cursive Script (草書).

Expression of Spirit (神韻, Shényùn):

Calligraphy is a reflection of the calligrapher’s inner character, emotions, and state of mind.

Japanese Calligraphy:

Simplicity and Spontaneity:

Heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, Japanese calligraphy values simplicity and naturalness.

Less focus on rigid structure and more on emotional expression.

Integration of Wabi-Sabi (侘寂):

Emphasizes imperfection and impermanence, allowing uneven strokes or irregular spacing to enhance the artwork.

Zen Influence:

Calligraphy often serves as a meditative practice. Works like Enso (円相), the Zen circle, embody these principles.

4. Common Themes

Chinese Calligraphy:

Famous for classical poetry, Confucian texts, and philosophical sayings.

The beauty often lies in how the characters themselves interact, with a strong focus on formality and elegance.

Japanese Calligraphy:

Frequently features Zen proverbs, haiku, or single characters with symbolic meaning (e.g., 無 [Mu, “nothingness”]).

Works often evoke spirituality or express fleeting emotions, reflecting the impermanence of life.

5. Style Comparison

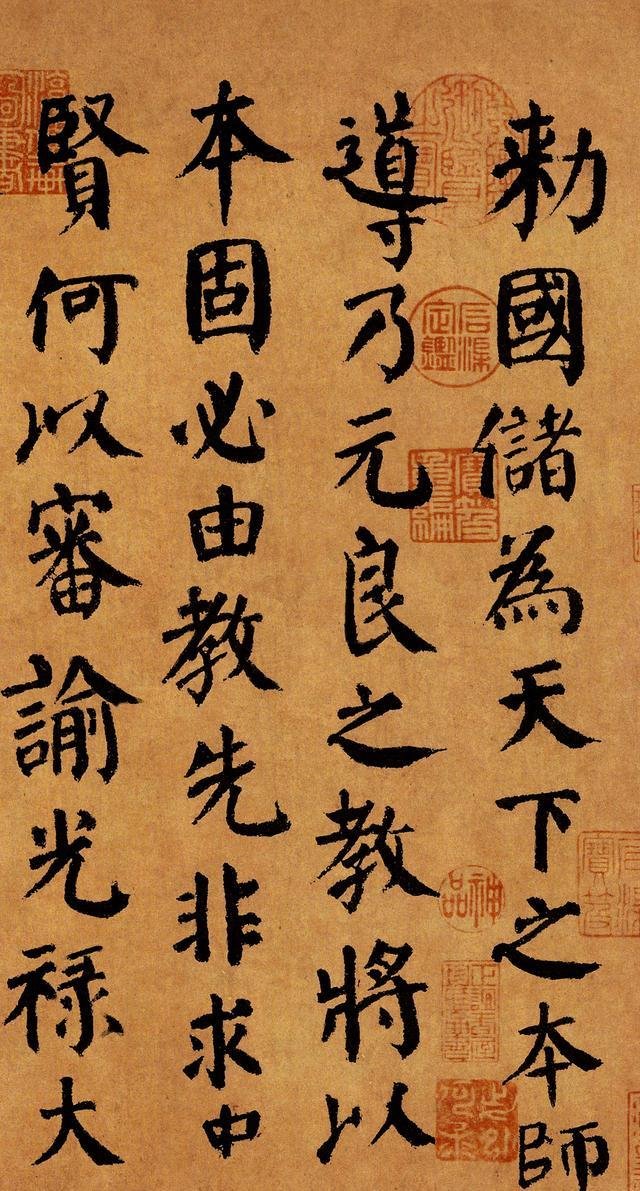

1. Regular Script (楷書)

Chinese Calligraphy:

Example: Yan Zhenqing (顏真卿) – Known for bold and structured strokes with a sense of strength and balance.

Style: Each stroke is precise, with careful attention to proportion and structure.

Visual Example: Duobao Pagoda Stele (多寶塔碑).

Japanese Calligraphy:

Example: Kūkai (空海) – Adapted regular script from Chinese influences with softer, rounder lines.

Style: More fluid and personal, often showing a gentler rhythm compared to the rigid structure of Chinese examples.

Visual Example: Sankei Mandara or Buddhist sutras.

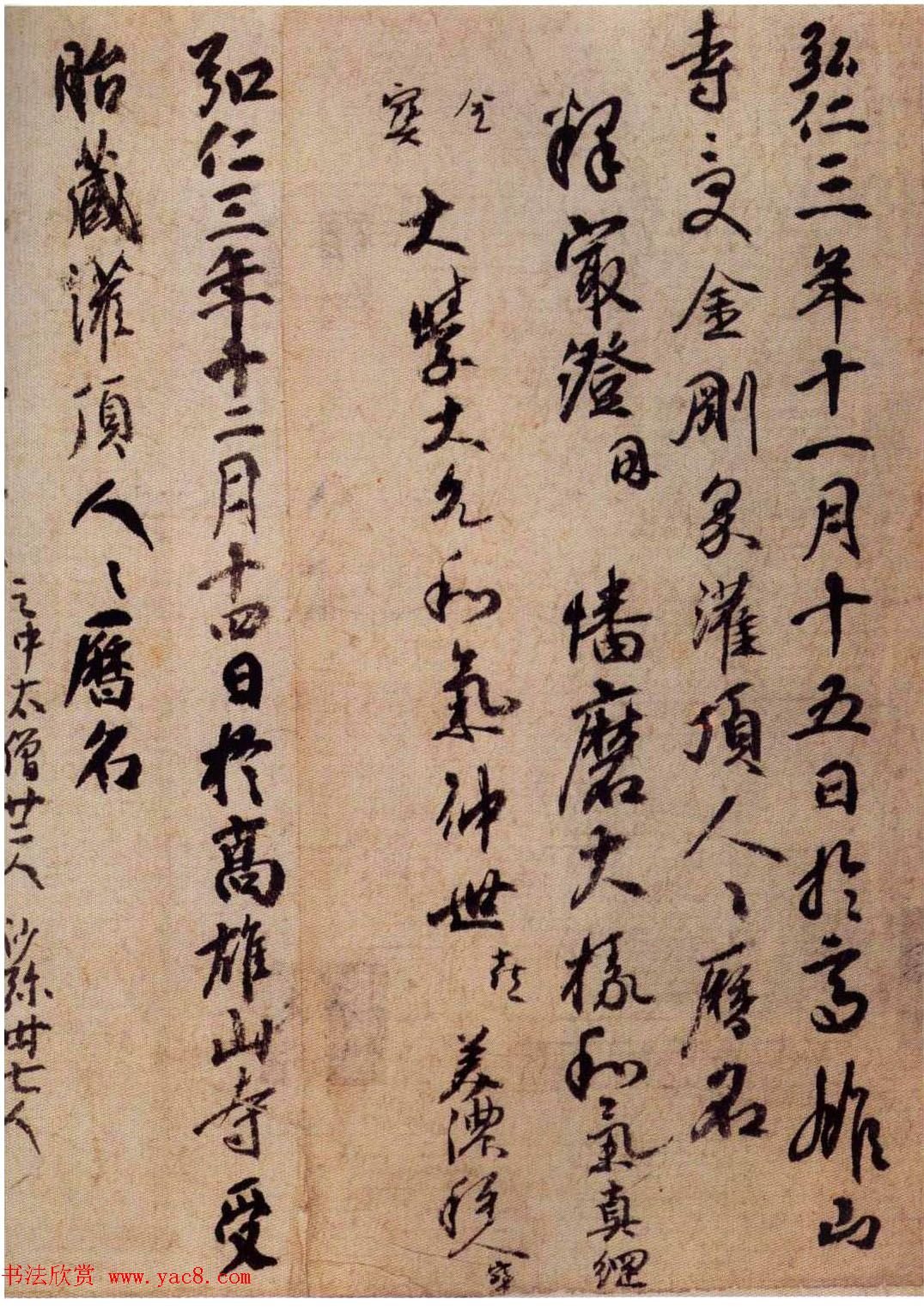

“Draft of the Eulogy for My Nephew By Yan Zhenqing (祭侄文稿 by 顏真卿)

Kanjō Rekimei by Kūkai (灌顶历名 by 空海)

2. Cursive Script (草書)

Chinese Calligraphy:

Example: Zhang Xu (張旭) – Wild and expressive cursive script.

Style: Exaggerated and highly dynamic, emphasizing spontaneity and emotional energy.

Visual Example: Autobiography (自叙帖) by Huai Su (懷素).

Japanese Calligraphy:

Example: Hakuin Ekaku (白隠慧鶴) – Zen-inspired cursive script.

Style: Minimalist and meditative, often focusing on a single character or phrase. It values emotional depth over technical perfection.

Visual Example: Zen koans or “Ensō (円相)” circles.

Four Ancient Poems by Zhang Xu (古詩四帖 by 張旭)

Anger Calligraphy by Hakuin Ekaku (怒り by 白隠慧鶴)

3. Zen Calligraphy

Chinese Calligraphy:

Example: Muqi Fachang (牧谿法常) – Zen master who incorporated calligraphy into paintings.

Style: Emphasizes fluidity and formlessness, blending calligraphy with traditional ink paintings.

Visual Example: Six Persimmons (六柿圖) – a simple yet profound painting with accompanying calligraphy.

Japanese Calligraphy:

Example: Hakuin Ekaku (白隠慧鶴) – Bold strokes with Zen proverbs or symbols.

Style: Minimalist and abstract. Works often reflect wabi-sabi aesthetics, such as imperfection and asymmetry.

Visual Example: A single character like 無 (Mu) or an Ensō (Zen circle).

Zen by Anonymous Chinese Calligraphy Artist

Japanese Zen Calligraphy by Tōrei Enji (無 by 東嶺円慈)

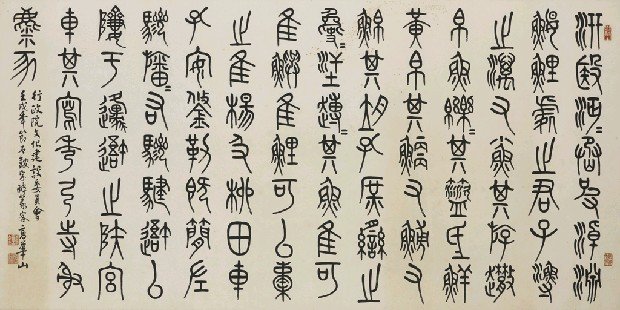

4. Seal Script (篆書)

Chinese Calligraphy:

Example: Qin Dynasty (秦朝) inscriptions.

Style: Formal and ancient, with rounded, intricate lines and uniform thickness.

Visual Example: Stone drum inscriptions (石鼓文) or imperial seals.

Japanese Calligraphy:

Example: Rarely used in Japan except for seals (印章, Inshō).

Style: When used, it is often a simplified version adapted from Chinese models.

Stone drum inscriptions Seal Script by Gao Huashan 篆書 by 高華山

6. Modern Influence

Chinese Calligraphy:

Maintains a strong cultural role in education, art, and philosophy.

Contemporary artists like Xu Bing explore abstract and conceptual interpretations of calligraphy.

Japanese Calligraphy:

Often experimental, blending traditional techniques with modern art forms.

Zen calligraphy, with its minimalist appeal, has gained global attention as a form of mindfulness and meditation.

While Chinese and Japanese calligraphy share a common origin, they evolved uniquely to reflect the cultural and philosophical values of each society. Chinese calligraphy emphasizes discipline, structure, and balance, while Japanese calligraphy prioritizes spontaneity, simplicity, and spiritual expression, particularly under Zen influence. Both traditions remain profound artistic forms that continue to inspire and influence artists worldwide.